COELENTERATES

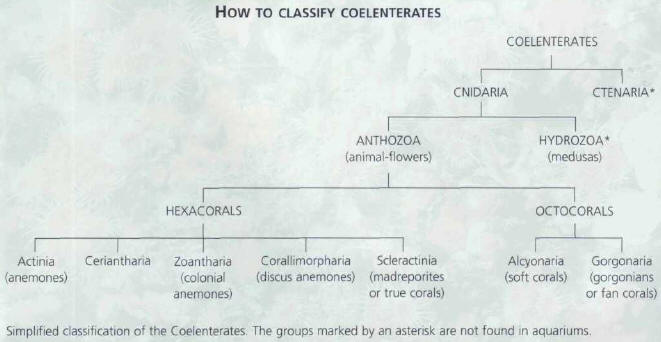

The Coelenterates constitute a complex group (see table, page 171). They include

the Anthozoa, which are divided into hexacorals, where the number of tentacles is

a multiple of 6, and octocorals, where the number of tentacles is a multiple of

8. The hexacorals are divided into:

- Actiniaria (true anemones);

- Ceriantharia;

- Zoantharia (colonial anemones);

- Corallimorpharia (discus anemones);

- Scleractinia (madreporites or true corals).

These invertebrates are characterized by tentacles attached to a foot, and the

whole organism is called a polyp. Anemones and Ceriantharia are isolated polyps,

while the other Anthozoa are colonial polyps, connected to each other at their base,

which end up by spreading out over large areas like certain plants.

Darts for defense

The bodies of Coelenterates, particularly the tentacles, are covered with urticant

(stinging) cells, equipped with a strand that is sensitive to contact with other

organisms. When a Coelenterate is touched, thousands or even millions of cells open

and eject a filament with a microscopic dart at the tip which injects venom; in

this way, a prey is quickly paralyzed before being eaten. Care should be taken when

handling, therefore.

Introducing Coelenterates to an aquarium

Coelenterates must of course present all the necessary signs of good health before

being introduced to an aquarium: they should be unfurled, swollen, and full of water.

If they are in a bad state, they look wilted and may not be viable.

Anthozoa like clear and well-lit water, as it benefits both them and the Zooxanthellae

to which they play host. They must be placed close to the surface of the aquarium.

The water quality is, of course, very important, and in addition the calcium levels

must be monitored with particularly close attention.

The skeleton of corals is mainly composed of calcium carbonate, which is abundant

in the natural habitat - up to 500 mg/liter - and so an aquarium that is to be inhabited

by corals must also have the same level.

The concentration in an aquarium can sometimes fall below 300 mg/liter, depending

on how many organisms there are in the tank, and in these cases calcium must be

added. Several relatively simple methods for raising the calcium level are detailed

in the box on page 173.

WHAT IF YOU TOUCH A COELENTERATE?

Some species have a greater stinging capability than others. Serious reactions,

such as cramps or breathing difficulties, rarely encountered among aquarists, can

be provoked by certain medusas (jellyfish), due to a phenomenon known as anaphylaxis:

the body is sensitized to the venom after an initial contact and becomes more vulnerable.

In the event of an accident, detach the tentacles and, above all, do not rub your

eyes. Treat the stung area immediately with diluted ammonia, but it is best to consult

a doctor.

Coral reefs

The accumulation of calcareous coral skeletons gradually forms reefs, of which

the most famous is the Great Barrier Reef, stretching north-eastward from south

Australia for almost 2,000 km. It is the biggest structure of animal origin in the

world! This ecosystem, one of the richest and most diverse in existence, is also

fragile and constantly subject to attack. The last few decades have witnessed the

destruction of some reefs, the coral being used to build houses, roads, and even

airport runways! Obviously, aquarists have been accused of taking part in this pillage,

which seems grossly exaggerated: the removal of corals from their natural habitat

for the aquarium trade does occur, but it is negligible compared to other largescale

extractions. Furthermore, some species are protected by law and never reach hobbyists'

tanks.

The leather corals of the Sarcophyton genus will not tolerate

being dose to Coelenterates highly prone to stinging.

Public marine aquariums can, on the contrary, make a contribution to the study

of invertebrates. The aquarium of the Monaco Oceanographic Museum, for example,

is carrying out research in this field, using a 40 m3 tank containing several tons

of corals, which are nurtured and bred. Until recently, raising corals on this scale

in captivity was impossible, above all because of their very great sensitivity to

nitrates (NO3-). Scientists solved this problem by allowing these nitrates to turn

into nitrogen gas (N2), thanks to the anaerobic bacteria which survive at the bottom

of the tank, where the oxygen levels are low. The nitrogen produced by the metabolism

of these bacteria then passes into the atmosphere.

This complicated technique is beyond the reach of most aquarists, however experienced

they may be.

|